Everything you ride is being electric, ready or not?

The world is ready for PEVs, but are PEV makers prepared for the world?

In 2009, 24/7 Wall St. made a list of “the 10 biggest tech failures of the last decade," which was posted in TIME magazine. One of the tech products on the list was Segway, a two-wheeled electric transporter that only sold 30,000 units from 2001 to the end of 2007.

The world is ready now

Shankman was right, sort of. No one would have predicted that Segway’s untimely demise would pave the way for the rise of micro-mobility vehicles, also known as personal electric vehicles (PEV). PEV refers to a range of small, lightweight vehicles including EUCs, E-Skates, Onewheels, E-Scooters & E-Bikes.

In recent years, electric transportation has had a tremendous growth spurt. Take the UK as an example: in October 2020, Halfords, the biggest UK cycling products retailer, reported a 450 percent boom in sales of e-scooters over the last three weeks, despite them remaining illegal on British roads.

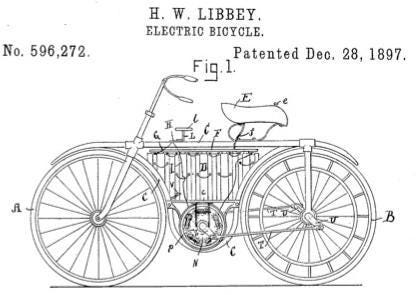

Despite being around for centuries (literally, since the first e-bike patent in the US was filed in 1897), e-bikes and e-scooters are just now picking up where Segways left off and might actually have the potential to “be to the car what the car was to the horse and buggy"—which is what the head of Segway called the product when they first launched. Unlike Segways, the now popular PEVs such as e-bikes, e-skateboards, and e-scooters have less of a “dork factor” and are more socially acceptable.

The rapid growth of PEVs reflects the pandemic in part. Historically speaking, people’s lives used to revolve around two primary locations: work and home. As WFM became a trend, people found themselves with more flexibility but tended to revolve around just one area. Let’s say someone who used to pick up groceries from a store near work now goes to a store near their house because they no longer have to go to the office. In such scenarios, they might choose a bike for the 5-minute ride because it’s not worth the hassle to drive and he can get some cardio done in the meantime.

Change is happening as a part of a larger movement, the green transformation. A study by the German Federal Environment Agency found that e-bikes emit only 5 grams of carbon per mile, compared to about 100 grams per bus rider and 240 grams per person traveling by car. Zhang Xi, founder of e-bike brand Velotric, which sold over 14,000 units last year, sees the transformation as a long-term trend rather than a temporary reaction to the pandemic. “I see a lifestyle revolution in the next 5 to 10 years,” says Zhang, who observed the market for around a year before launching Velotric.

The kind of lifestyle revolution that Zhang described is spreading. PEVs, although vastly dominated by the younger population, are no longer exclusively for young people. 70-year olds and 80-year olds are looking to buy e-scooters, according to Joshua Frisby, the founder of Electric Scooter Insider, an e-scooter review website, who received emails from elders asking for recommendations. “They're maybe not as able as they were before, and they want a scooter to get around easily. It gives them a bit more freedom.”

BoYi, an expert in the industry and founder of BoYi KuaJing - an cross border e-commerce company, also found that elderly people who wish to appear young and able are buying e-bikes, especially the ones with undetectable batteries that look just like regular bikes.

Are the brands prepared?

As the market booms, comes the tale old as time: people rush into the market and create more supply than demand. Brands descended as quickly as they had risen. Even Rad Power, the leading e-bike brand in North America, suffered three rounds of layoff in the past year.

Currently, the market penetration rate for e-bikes is about 20% in Europe and 4% in the US. According to Market Study Report, LLC, the worldwide e-bike market was valued at USD 25.03 billion in 2020 and is projected to expand at a CAGR of 9.95% over 2021-2028, and reach a valuation of USD 48.46 billion by the end of the forecast period.

The surviving brands are looking for a sustainable way of development, and they need to find their core competence in order to do so.

Many PEV projects have emerged on crowdfunding website Indiegogo, and “”motorcycle-inspired”, “smart”, ”foldable”, “affordable” are the most frequent key words in these campaigns. The industry has entered a red ocean competition on the international market, characterised by extreme homogenization, which narrows the profit margin for brands.

Urtopia is a high-end e-bike manufacturer with headquarters in Hong Kong. Owen Zhang, the CEO of Urtopia, defined the present profit allocation in the market as a "4-4-2" ratio, with 40% going to suppliers, 40% to distribution channels, and just 20% to the brands. According to Owen Zhang, the optimal proportion would be 2-2-6, with 60% going to brands.

In order to play it safe, Chinese brands, which take up a big portion of the budget PEV market, tend not to emphasize or avoid mentioning their Chinese identity, due to the “Chinese products are cheaply built” stereotype. In a way, they white-label themselves (yes, pun intended) by registering overseas or establishing overseas headquarters. According to Joshua Frisby, however, such preconceptions are no longer prevalent, at least in the area of micro-mobility vehicles, which is relatively young and where Chinese companies have already dominated.

Budget scooters, which account for the largest share of the market, are largely dominated by TurboAnt, a Chinese brand. In addition, the light of the performance scooters made up a lot by Kaabo, also a Chinese brand, said Frisby.

Straight outta OEM

Frisby reckoned that buyers of such products tend to be more tech savvy and prefer to critically examine the numbers/performance and how they deliver across metrics as opposed to the brands' origins and narratives. “With models that are OEM, for instance, they will be seen as being of lesser quality than another brand that is doing a proprietary mold or proprietary design,“ says Frisby.

Jack Hsu, who runs the Toronto e-Riders, a PEV enthusiast club with 3,194 followers on Facebook and the YouTube channel Electric Dreams, agrees that the OEM route and white-labeling can only get you so far, whereas proprietary localization and brand management are the way to go.

Hsu, who also works as a consultant for micro-mobility brands, says he hopes that companies will study the markets that they serve more closely and localize products based on users’ needs.

For Hsu, the top determinant for the quality of a ride is how smooth it can be, which depends on the sensor. There are generally two types of sensors on the market, the torque sensor and the cadence sensor. Simply put, the former determines how much power to feed the bike based on pedaling intensity, while the latter depends on pedal speed. Torque sensors often offer a more intuitive riding experience.

Fine tuning the sensors on a vehicle to create a balance between how much electric power is put into the vehicle and how much is done by pedaling contributes greatly to the user's experience, which is why he feels brands need to pay more attention to details and put in more groundwork.

PEV brands find OEM and proprietary to be a question, for different reasons than how consumers perceive the two routes. The OEM route is more cost efficient for startups with low funds, yet with limited manufacturer options, brands often find themselves dealing with unreasonable high prices.

War of Motor

According to an e-bike brand, Bosch currently offers the most reliable e-bike drive systems in the world, and Bafang, a Hangzhou-based company, dominates in China. Brands often choose between the two based on the market they sell to. Bosch is a pioneer in making mid-drives, which are electric-assist motors on e-bikes that drive through the pedal cranks. Bosch mid-drives are found in many high-end e-bikes in the European market, where the legal limit is only 250 watts, but the limit on US bikes is 750 watts, and many e-bikes sold in the US use Bafang hub-motors, which often help to save weight.

European countries tend to have more complete bike lanes, whereas the infrastructure in the US would favor cars, which results in European consumers wanting e-bikes for commuting in the city and US consumers wanting them for outdoor activities.

In addition, the cost of the two different types of drives also plays a crucial part. Roughly speaking, a Bosch drive would add an additional 300-400 USD to the cost per unit compared to a Bafang drive.

“People don’t buy from Bafang because they are good,” says a person familiar with the situation, “People buy from Bafang because there aren’t too many competitors in the realm, and they can’t afford Bosch. “

Batteries, motors, and electric control systems are the three most crucial and fundamental components of PEVs. Other than that, smaller parts can also lead to big hassles. Take the experience of a PEV manufacturer: He bought a batch of brakes from one of the top 3 manufacturers in China in terms of shipment volume and found them to be defective—the factory did a poor job on quality control, and the brakes only activated when being pressed quickly.

“When you just buy parts from manufacturers and piece them together, they are bound to have poorer quality and performance,” says Zhang.

Innovation comes in time

Velotric is taking the proprietary route. According to Zhang, Velotric plans on building two E-bike platforms, one for budget bikes and one for performance ones. Zhang, a Lime veteran who used to serve as hardware cofounder at the company described the platforms as the basic structures for any bikes the company might launch in the future. It took Velotric’s team - which consists of many Lime and Didi veterans - around 10 months to build a platform.

The time and resources put into the R&D process are worthwhile, according to Zhang, as he considers that what current manufacturers and OEM models have to offer doesn’t meet high standards in an affordable price range.

Low quality, high prices, and wasted time and energy have pushed brands to pursue proprietary designs, and their innovation doesn’t stop at the fundamentals. As competition grew fierce, brands were looking to add transparent displays, fingerprint locks, and digitization designs such as remote control apps to their products, as well as expand their product lines. For example, the e-bike brand Nakto is developing a food delivery e-bike in the US.

Innovation comes from observation, which is why brands are trying to approach their consumers by setting up dealerships and after-sales services overseas.

Nakto is in the process of opening its own dealerships in the U.S. “We used to work with local dealers,” said Aston Zhu, founder of Nakto, who acknowledged the importance for buyers to test the vehicles before making a purchase, “It can cost a great deal to put our bikes in a shop just so buyers can see the bikes in person.”

“We need to go out there instead of making judgments based on second-hand, obsolete information,” said Zhu.

This is the next step Chinese PEV brands must take in order to leave their "comfort zone" (budget markets) and explore premium markets. The PEV market is expansive and ripe with opportunity, and companies must take a leap of faith whether they are offering exclusive design or working on brand management and localization.

Writer: Zijing FU